Alternative title: A Character Study in Why I Hate Social Media

Social media killed the fitness magazine—and the internet just watched. Today I want to take stock and talk about the humble fitness magazine. When were fitness magazines first sold, why did people buy them and why, ultimately, did people discard them. While it may seem funny to talk about a relatively dead medium outside of a handful of magazines (Men’s Health, Men’s Fitness etc.) I’m currently writing an article on Health & Strength, the British fitness magazine which ran from 1898 to the 2010s and it has forced me to really think about the value magazines had for weightlifters across generations.

Three Waves of the Fitness Magazine

Magazines dedicated to physical culture, gymnastics and/or callisthenics can be traced to the first half of the nineteenth-century. In one of the few academic studies of the fitness magazine Jan Todd, Terry Todd and Joe Roark meticulously listed Anglophone magazines dating from the early nineteenth-century to the present day. Now few historians worth their salt would say that fitness magazines were important in the early 1800s, but none would deny their importance in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Thanks to a combination of factors ranging from cheaper shipping/postage rates, improvements in photography and printing and faster transport options, the first great magazine ‘boom’ came at the dawn of the twentieth-century. Coinciding with the rise of the physical culture movement – which was effectively the birth of modern health and fitness cultures – magazines on health, strength and fitness were printed across North America, Europe and parts of Australasia.

What is so cool, and maybe unexpected, for people is that these magazines were read everywhere. Thanks to colonial, imperial and trading networks British and American magazines could be read in Africa, Asia and other parts of the world. It was a true and enthusiastic lifting community. Even warfare couldn’t stop the first wave of magazines. During the Great War (1914-1918) some magazines, like the British Health & Strength magazine, printed on cheaper paper, determined to keep spreading the gospel of health and fitness.

So the first ‘wave’ of fitness magazines came in the early 1900s. I am going to be somewhat lazy, or controversial (pick your poison) and say that the next great wave did not come until after the Second World War. It was during this time, especially in the American context, that entrepreneurs like Bob Hoffman and Joe Weider began to produce glossier fitness magazines centred around one training modality like weightlifting or bodybuilding. While ‘first wave’ magazines were ‘physical culture’ magazines, meaning that they focused on a range of health activities, second wave magazines were defined as bodybuilding or weight lifting magazines. They were more specialised and more polished in their execution.

The final wave, before the floor truly fell out of publishing, came in the 1980s and early 1990s when more lifestyle focus magazines emerged for men and women. Think the like’s of Men’s Health which combined training advice with more generic advice about watches, skincare, sex etc. More defined muscle mags still existed, and for a while, thrived, but there was a new format which some followed.

Now this rough history is very much that. Rough. Some magazines, like Health & Strength in England, adapted and lasted through each wave but for now, this general history is good enough. And good enough is what kids? That’s right… it’s what I specialise in.

Why am I giving you this history? Because magazines were important and, as we’ll see, the shift from magazine to online content has significantly changed the nature and culture of fitness.

What Magazines Got Right

We’ll begin with the positives shall we? Because I am not blind to the problems with fitness publishing.

In the first instance magazines provided curated, expert advice for your chosen sport. If you wanted to be a better powerlifter, Powerlifting USA had routines and interviews with some of the leading athletes in your sport. In other magazines you had readers submit their own routines or, in the case of bodybuilding magazines, you had entirely made up routines attributed to champion bodybuilders. Don’t get me started on the Men’s Health routines… so some bizarre balancing act where I press dumbbells overhead while squatting on one leg will get me ‘jacked for the summer’? Gotcha.

Wait I thought I was going to be positive… Okay outside of bodybuilding and men’s lifestyle magazines, many powerlifting, weightlifting and even counter-cultural muscle-building magazines (like Hardgainer) were very useful sources for fitness routines, diets and psychology. Across all ‘iron sports’, magazines were an important source of gate-keeping. You learned who the experts where because they were the ones publishing, writing and being interviewed.

Was this abused? Sure. Editors had favorites and agendas. But can you really say the democratization of information online has led to better overall information. Go ahead… I’ll wait.

So magazines helped to centralize knowledge but they also helped to centralize role models. One of my favorite memories in the archive was seeing images of a young Reg Park in Health & Strength magazine and lining up his various cover images over the next several decades. Fitness magazines told you who the experts were but they often traced transformations over several years. I’m going to remain positive here before going negative.

Magazines also helped to create core followers which, critically, were moderated heavily. Letters to the Editor and reader’s groups were rigidly moderated. Letters were censored, or not published. If you went to a Strength & Heath reader event, as sometimes happened in 1950s America, you would adhere to the magazine’s behaviour guidelines. There was far less toxcitiy around fitness camps because of their simply wasn’t the chance to be toxic. Additionally because fitness magazines were decidedly fitness magazines, actual conscious choices had to be made about what behaviour was tolerable. It was far trickier to bring culture war debates into print (although it did happen from time to time).

So fitness magazines informed, taught and gave role models. They also helped to structure ideas about supplementation and diet among other things. Finally they, critically, kept information relatively static. Stay with me on this one. Even if magazines always published ‘cutting edge’ research, which they didn’t, they only did so every two weeks or every month. This meant a relatively slow rate of change over time rather than something becoming an overnight sensation based on some tasty online videos… I’m looking at you lengthened partials.

What They Got Wrong — And Social Media Perfected

And ironically what social media tended to learn from fitness magazines.

So first off, magazines lied. A lot! Regardless of the ‘wave’ magazines and magazine editors promised readers that the next great supplement, workout or combination of the two, would change their lives. Worse still, they lied about people’s genetic potential.

Listen I’m all for the ‘work hard and never put limits of yourself’ mindset but the reality is some people are built differently. I have worked my ass off to get to a 450lbs. plus deadlift. Is that impressive? For me, absolutely. For Ed Coan, one of the world’s greatest deadlifters… not at all. When Ed was 16 he was pulling nearly 500 lbs. in the deadlift at a lighter bodyweight. Ed, to be fair, has never said that anyone can emulate him, but many magazines did, and continue, to promise the ability to be the next Ed Coan, Ronnie Coleman, Callum Bumstead etc if they just tried hard enough.

What about Eugen Sandow, the early 1900s physical culturist? He promised that anyone could perfect their physique using his patented system of light-weight dumbbells. The reality is that some people find it easier to build muscle and lose fat. Some are better placed for powerlifting versus weightlifting. Some people have 8 packs when they’re lean, and others gotta 1 pack. Does this mean we should stop trying? Of course not, but rather that we should have nuance in terms of what is possible for people.

But the lies Conor, the lies! The bigger lie of course was not about achieving genetic potential but rather how the people featured in the magazines achieved their potential. From the 1950s, Anglophone magazines began featuring enhanced athletes. Editors, as John Fair’s wonderful article showed, often linked the muscle and strength benefits of steroids to new supplements. So rather than saying athlete X took Dianabol and gained 10 pounds of muscle, they said athlete X took ‘Joe Weider’s patented mass gainer’ and gained 10 pounds. No mention of steroids or, in a particularly harmful ploy, downplayed the effects of steroids altogether.

This created a warped picture of what was naturally achievable. And it was reinforced across covers, captions, and carefully curated training plans that were either total fabrications or omitted the pharmaceutical support that made them possible. It wasn’t just misleading—it was demoralising for average lifters chasing unattainable goals.

Then there was the issue of repetition. As magazines chased monthly sales, content often became formulaic. You’d get the same advice rebranded with new buzzwords: “shock your muscles,” “blast your plateau,” “get beach-ready in four weeks.” It became harder to separate marketing from meaningful guidance. Useful routines and deep-dive interviews were there—but you had to dig through the detritus to find them.

Enter Social Media: Faster, Flashier, and More Complex

Social media inherited these problems and magnified them—but it also created new possibilities that magazines never could.

The false promises didn’t go away—they just got louder, shorter, and more algorithm-friendly. But now, instead of being peddled by a monthly editorial team, they’re delivered daily by influencers with discount codes, lighting tricks, and access to an endless stream of engagement-hungry followers.

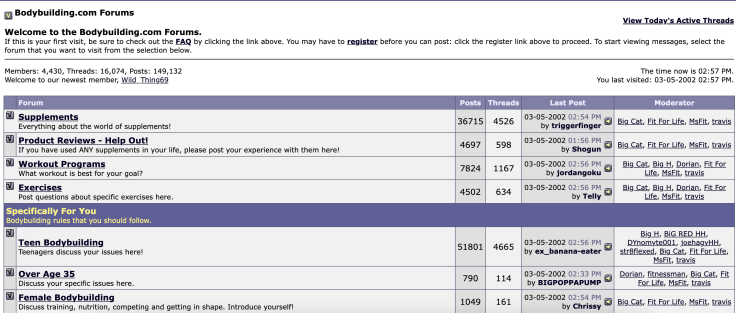

Where magazines at least offered editorial filters (however flawed), social media offers none. Anyone can be a coach. Anyone can sell you a dream. Expertise is replaced by visibility. The guy with the ring light, the tight shorts, and the viral edit becomes the authority.

Yet this democratization has genuine benefits that magazines never provided. Women’s powerlifting has exploded partly because female lifters could bypass traditional gatekeepers and build their own communities. Coaches from non-Western training traditions can now share methodologies that magazines—dominated by Anglo-American perspectives—rarely featured. A lifter can post a squat video and receive technical feedback from multiple experienced coaches within hours, something impossible in the magazine era.

The algorithm problem is real, but it’s not universally terrible. Yes, it promotes flashy content, but it also enables niche communities to form around specific training methods—powerlifters finding advanced programming discussions, mobility specialists sharing detailed movement breakdowns, adaptive athletes connecting across geographical boundaries.

Some social media fitness creators have built more comprehensive educational resources than entire magazine archives. Coaches like Dr. Eric Helms break down exercise science with academic rigor, while platforms like Instagram allow for detailed technique demonstrations that static magazine photos couldn’t match. The medium has also forced more transparency—while magazines could quietly omit steroid use for decades, social media’s immediacy makes such deception harder to maintain.

But the social dynamics are fundamentally different—and often worse. Magazines built communities—however imperfectly—through moderated letters pages, subscriptions, and organized events. Today’s fitness “communities” run on algorithms and outrage. The cost of entry is low, but the cost of staying sane is high.

The result? A paradox. More access to quality information than ever before, but also more confusion, burnout, and endless churn. One week it’s knees over toes, the next it’s lengthened partials, then blood flow restriction, then reverse Nordic curls. What was once a trickle of information, slowly digested, is now a firehose of contradictory advice—and the average lifter drowns in choice.

So Why Does It Matter?

This isn’t nostalgia for the sake of it—it’s about understanding what we’ve gained and lost in this transition, and what we might reclaim.

Fitness magazines weren’t perfect—far from it—but they operated in a different mode. They asked you to slow down. To think. To follow a 12-week plan and see how it went before moving on to the next. They told you who the experts were and gave you time to learn from them. When they were good, they built archives of knowledge rather than moments of engagement.

Today’s fitness landscape is louder, more fractured, and less forgiving—but also more accessible, diverse, and transparent. Social media has removed many of the barriers to entry, giving voice to previously marginalized communities and training approaches. The challenge isn’t returning to the magazine era, but figuring out how to preserve its contemplative, long-term approach while maintaining democratic access.

What would a ‘slow fitness media‘ movement look like? How might we rebuild expert curation without excluding diverse voices? Some answers are already emerging: subscription platforms that combine expert oversight with community interaction, long-form content creators who deliberately slow down information cycles, online communities that enforce behavioral standards through thoughtful moderation rather than algorithmic chaos.

The iron game has always been about patience, consistency, and long-term thinking. The best of the magazine era understood this. The challenge now is teaching these values to a medium built for speed and instant gratification—because the alternative isn’t just bad information, it’s abandoning the very qualities that make strength training transformative in the first place.

So yes, I miss fitness magazines. Not because they were pure, but because they understood that real progress happens slowly, in the spaces between the noise. The question isn’t whether we can return to that era—we can’t. It’s whether we can learn from it.

As always… Happy Lifting!

I have all my issues of Powerlifting USA and MILO in a bin at my gym, great article!