When Did Everyone Start Looking Like This?

I did not go looking for F. A. Hornibrook.

He turned up while I was chasing something else, which is usually how these things happen. A name in an advertisement. A reference that did not quite make sense. A photograph that looked familiar in a way that was hard to explain. He never arrived all at once. He just kept reappearing.

Hornibrook was Irish. He left, as so many did, and by the late nineteenth century he was in New Zealand and later Fiji. At some point along the way he decided, or realised, that he could make a living teaching physical culture. He ran classes. He trained men. He wrote about exercise and health with the quiet certainty of someone who assumed the reader was already half convinced. I do not remember exactly when he started to stick with me, but it was not because of anything especially dramatic in his writing. It was the photographs.

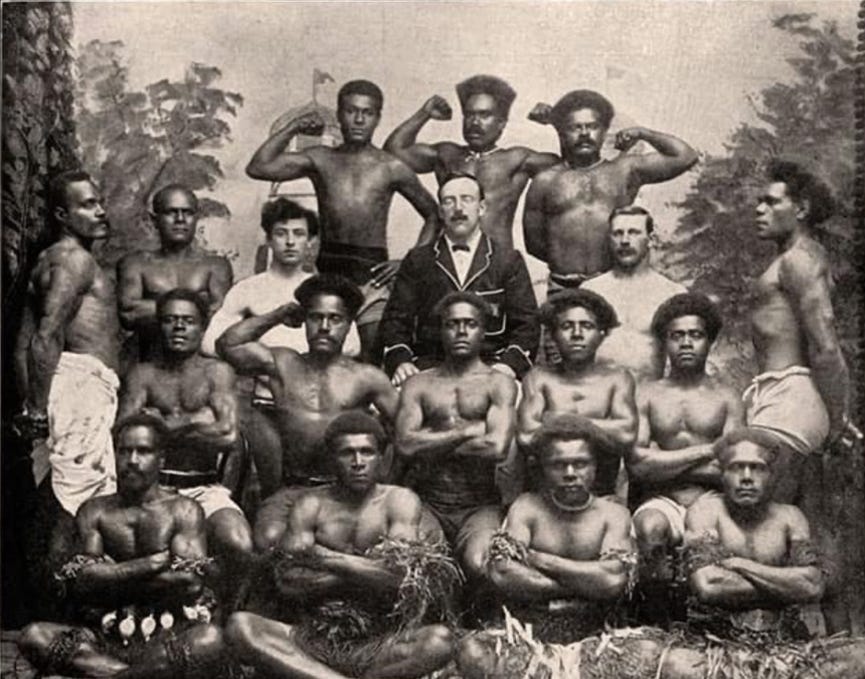

There is one image that I kept coming back to. Hornibrook stands beside a group of his trainees from the mid-1900s. Everyone is barefoot. Everyone looks serious. Nobody looks especially comfortable. The bodies are trained but restrained. No one is straining. No one is trying to impress the camera. The posture is doing most of the work.

The first thing I noticed was that the bodies were not remarkable.

That sounds odd, given the context. These were men being trained in Fiji at the turn of the twentieth century, photographed as evidence of a successful physical culture system. Specifically Eugen Sandow‘s physical culture system. You might expect something more striking. Something exoticised. Something clearly different. Instead, what you get is something very ordinary. If you cropped the background and removed a few clues, the photograph could sit almost anywhere. A gym in Britain. A YMCA space in the United States. A school hall in Australia. The bodies do not seem anchored to place. That bothered me more than if they had looked unusual. Hornibrook was training men whose daily lives were very different from the men reading about physical culture in Britain or Ireland. Different work. Different food. Different rhythms to the day. And yet the bodies he chose to show looked as if they belonged to the same narrow category. Upright. Balanced. Controlled. Strong without excess.

I kept noticing the same thing elsewhere, though it took a while before it registered properly. Swedish gymnastics manuals. British school drill photographs. American mail order fitness courses. Different systems. Different explanations. Different language. The bodies kept arriving at roughly the same place. Lean rather than bulky. Muscular but not exaggerated. A sense that the body should look capable without needing to prove it.

Once you see that, it is hard not to keep seeing it. Hornibrook was not unusual in what he taught. That is part of the point. His writing sits comfortably alongside dozens of other physical culture instructors of the period. He talks about posture, breathing, moderation, regularity. The body is something that needs attention and guidance. Left alone, it will go wrong. There is a moral tone to this, even when it is not stated outright. Stand properly. Move properly. Do not overdo it. Strength is acceptable so long as it behaves itself. That idea was already everywhere by the early twentieth century. It is tempting to explain this as science doing its work, as if people simply discovered better ways of training and everyone sensibly followed along. The archives do not really support that. What you see instead is repetition. Exercises borrowed and rebadged. Ideas lifted from one context and dropped into another. Photographs posed in very similar ways, often by people who had never met. Bodies learning how to be read.

Hornibrook did not invent that. He inherited it. He learned it from the same books, magazines, and systems circulating at the time. What he did was carry it with him and reproduce it elsewhere, probably without thinking very hard about how specific it already was. That specificity hides behind the language of moderation. The ideal body promoted by physical culture at this point sat in a very narrow range. Too thin suggested weakness. Too fat suggested moral failure. Too muscular suggested excess, vanity, or something faintly suspect. The acceptable body was disciplined. Controlled. Visibly healthy but never unruly.

This is where the photographs start to feel less innocent. Physical culture has always been about more than health. It is about how bodies appear in public. About what they signal. About who looks reliable, respectable, capable. In colonial settings, this took on additional weight. Bodies were already being judged and categorised in countless ways. Physical culture offered a way to present oneself as modern and controlled, even when other markers worked against you. Hornibrook’s trainees were not just being taught how to exercise. They were being taught how to stand, how to hold themselves, how to look right. I do not think Hornibrook saw himself as imposing anything. His confidence reads as genuine rather than aggressive. He believed what he was teaching was sensible. Useful. Almost obvious. That belief mattered.

Physical culture spread so effectively because it did not feel forced. It felt reasonable. Of course posture matters. Of course breathing matters. Of course the body needs to be trained rather than ignored. These ideas slip in easily because they do not announce themselves as ideology.

By the time Hornibrook was working in Fiji, the shape of a good body had already been agreed upon in many places. Not formally. Not explicitly. It had simply settled.

When I look again at that photograph now, what strikes me is not the strength on display but the care. The bodies seem cautious. As if they are trying not to overstep some invisible boundary. Strength is present, but it is being managed. That balance is still with us. Modern gyms feel familiar across countries not just because the equipment is similar, but because the bodies moving through them are chasing the same cues. The same postures. The same visual signals of effort and control. Even attempts to reject these norms tend to orbit them. Hornibrook did not create that world. But he lived comfortably inside it. And through people like him, working quietly and confidently far from the usual centres of power, the idea of a correct body spread and settled. There is something unsettling about how little those old photographs need explaining. Not because they look modern, but because they feel immediately legible. We know what we are supposed to see. Hornibrook is easy to overlook in the archives. He does not demand attention. He does not come with a ready made story. But once he gets under your skin, he stays there. Not because he was exceptional, but because he was ordinary in exactly the right way.

And that is usually where these things are hiding.

As always... Happy Lifting!